MPs were told yesterday of how residents took control of a bankrupt retirement village, raised £2 million and turned it into the first mutually owned retirement site in the country.

MPs were told yesterday of how residents took control of a bankrupt retirement village, raised £2 million and turned it into the first mutually owned retirement site in the country.

Professor Peter Wilson told the Campaign against retirement leasehold exploitation / LKP roundtable, hosted by the charity’s MP patrons Jim Fitzpatrick and Sir Peter Bottomley, that the initiative was forced on the residents after the developer went bust.

The audience included key figures from the Leasehold Advisory Service, the civil service, the Law Commission, lawyers, trade bodies, retirement housebuilders, property managers and leaseholders. They included Campaign against retirement leasehold exploitation co-founder Melissa Briggs, who ran the campaign until 2012 and who remains a trustee of LKP / Campaign against retirement leasehold exploitation.

But long before the site now known as Woodchester Valley Village, near Stroud, went bust it was deteriorating fast, although fees weren’t.

Professor Wilson said:

“It soon emerged that the developer was more focused upon the profits of new build, and the ten per cent transfer fee he could collect whenever his tenants departed, than upon maintaining cost effective services and maintenance.

“Why should he worry about cost effectiveness when however much he spent he could add 10% for profit? The bigger the spend, the greater his profit.”

In 2010 the developer went bust, but Professor Wilson, who held the chair in management at Bedfordshire University, “was determined to take back control of my life”.

The Wilsons had bought an end of terrace house in the village on the insistence of Mrs Wilson in 2006.

“At the time I was dragged screaming into our retirement village but I now realise that my wife was right,” Professor Wilson told the roundtable. “The time to benefit from retirement living is 70 or soon after. Not waiting until 80.”

Taking back control meant buying the village with the help of residents aged 67 to 90 of limited means, although most residents have pensions of £25,000 a year.

“The key to our success was the fact that we had the support of the families of the residents who dug deep into their professional experience and made some dig even deeper into their pockets.

“That is how we managed to raise £2 million, and I now wish we had raised £3 million as like any new business you always need a little bit of extra cash.”

A particular concern of the residents was the 10 per cent exit fee on sale, which was reduced to 1 per cent provided they gave an interest-free unsecured 5 per cent loan of the equivalent of their purchase price.

That raised almost £1 million, and another £750,000 was raised in unsecured loans from a few residents and their families at 6.6 per cent with “hope of early pay back if we could sell off peripheral assets”.

“We finally got support from 90 per cent of the leaseholders that mutuality with no shareholders was a great idea, even though an unproven idea.

“In the end only 4 leaseholders refused to join in. Importantly, we involved the staff throughout the process. They were partners in our social enterprise.

“The greater challenge was convincing the main creditor, a Swiss bank, that we were capable of managing ourselves, and under our management they had a better chance of recovering some of their loans made to the former freeholder. That took some time, but here again the families rallied round offering professional resources – accountants, surveyors, solicitors, interior designer.

“After almost three years of hard work on Trafalgar Day [October 21] 2013, the bankers agreed to our suggestions, and we went mutual with a not for profit company owning the freehold.”

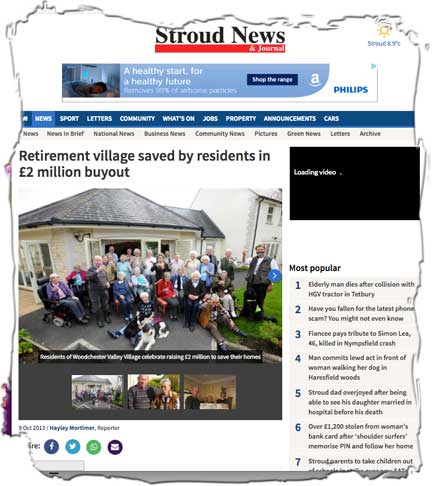

Owning and controlling their own retirement village has brought a considerable sense of freedom to the residents of Woodchester Valley Village.

Professor Wilson said: “There is nothing wrong in developers making a profit from retirement housing but they do need to rethink what are their customers’ needs, if they are to attract the active retired.

“Leasehold retirement villagers need the assurance of special legislation, separate from current leasehold law, which empowers them to manage their chosen life style.

“Otherwise, we may have to accept the alternative which is that retirement villages are just ghettos, half-way houses, for the physically and mentally infirm who can be easily overcharged.

“I would have loved to have raised the money as well Bob Bessell does and have built the village from scratch. I would then have had a management structure in place that would have given the residents control of their lives from the start.”

Professor Wilson’s full paper for the roundtable is below

Subject: RE: Commons.

Good afternoon

Important issues affecting the development of retirement housing in the UK have already been raised, and I would like to add to them.

For me, a person who has experienced the worst and the best of living in a retirement village, the key issues are the total unsuitability of current leasehold law, which was designed for a different set of circumstances, and the often, and for understandable and seemingly rational reasons, the unintentional, I hope, removal of rights from those who commit themselves to buying a retirement home.

However, I was asked to talk about the unique Woodchester Valley Village. At the outset may I explain that the village is for those who have assets and net income say at least £25,000 a year.

A Social enterprises

At Woodchester we have created a mutual, not for profit, social enterprise. The village has two simple aims. Firstly, to provide an environment in which to enjoy an active retirement, and, secondly, for later in life, to provide support services to sustain independence, and so dignity, for as long as possible.

Origins of the village

The village, created in 2002, was the product of a developer with vision. Those who have looked at our website will know it has 72 homes ranging from studio flats, through terrace housing, to four bedrooms detached homes. Importantly most have their own front doors to open space. These are a critical factor to which I will refer later.

Move at 70

A decade ago, when I was 70, my wife persuaded me that our hillside garden would become beyond our capability to maintain. I emphasise ‘would become’. At the time she said ‘was’.

My wife urged that we addressed our possible needs fifteen years forward rather than wait until they arose and when we unable to make our own decisions about our lives or indeed of managing the process of moving house. She added ‘and we are only moving once’

So we bought in 2006 a three double-bedroomed end of terrace house, with a conservatory for growing plants, where the village management offered property and garden maintenance and, for the longer term a restaurant for meals, twenty-four-hour on-site staffing for care, gardens to relax in, and a minibus to take us about when we could no longer drive. On holiday, our home would be cared for.

The choice of property was central to the lifestyle we wanted at 70, but sustainable at 85 plus. The active elderly do not want small flats. They expect space to entertain – family and friends – and to continue their hobbies.

I now realise she was right the ideal time to move into and benefit from the freedoms of a retirement life style is in the early 70s.

Profit before lifestyle

Regrettably, our choice, although almost right in terms of property, was defective.

It soon emerged that the developer was more focused upon the profits of new build, and the ten per cent transfer fee he could collect whenever his tenants departed, than upon maintaining cost effective services and maintenance.

Why should he worry about cost effectiveness when however much he spent he could add 10% for profit? The bigger the spend, the greater his profit.

Soon after we moved in and the last new property was sold, fellow residents began to feel exploited. They felt that maintenance was not good, the gardens were suffering, charges could not be justified, and the quality and range of services was declining.

A maintenance backlog was developing and no funds seemed to be available. The Residents’ Association confronted the issues and in the quagmire of leasehold law spent money and personal time, yet made little headway.

In 2010 the developer/private landlord ran out of funds and the creditors closed in. In administration speculators circled the village. By then chairman of the Residents Association, I was determined to take back control of my life.

As we could not sell our home (would you have let your parents buy into the village, not knowing who owned the freehold?) I decided that we must buy the village.

Fortunately, my background experience helped.

Our solution

It was a long process, requiring commitment and perseverance.

Ultimately, faced with the alternatives, the response from my fellow residents, aged 67 to 90 and with limited means, and fearful they would not be able to sell their home to meet the cost of possible terminal care, was fantastic. However, without the support of some of their families who dug deep into their pockets, we would not have raised the money required.

For the elderly leaseholders their concern was the 10% transfer fee, so I proposed to reduce it to 1% for those who offered an interest free long-term loan roughly equivalent to 5% of the purchase price they had paid. That helped towards raising almost £1m, but left us well short of what we needed.

Another £¾m was raised in unsecured loans from a few residents and their families at 6.6% interest but with a hope of early pay back if we could sell off peripheral assets. What was sought was serious financial commitment to an idea.

We finally got support from 90% of the leaseholders that mutuality with no shareholders was a great idea, even though an unproven idea.

In the end only 4 leaseholders refused to join in. Importantly, we involved the staff throughout the process. They were partners in our social enterprise.

The greater challenge was convincing the main creditor, a Swiss Bank, that we were capable of managing ourselves, and under our management they had a better chance of recovering some of their loans made to the former freeholder. That took some time, but here again the families rallied round offering professional resources – accountants, surveyors, solicitors, interior designer.

After almost three years of hard work on Trafalgar Day [October 21] 2013, the bankers agreed to our suggestions, and we went mutual with a not for profit company owning the Freehold.

From scratch we had to establish protocols and procedures to manage our estate, our staff of 16, and, most importantly, to create strategic structures to enable everyone to be part of the decision-making processes without empowering 72 leaseholders individually to give orders to staff, especially the gardeners.

You are well familiar with the conflicts within voluntary groups where all have equal rights and all may have different opinions. Our group was an involuntary group forced together in adversity.

Managing individual leaseholders was and still is a skill demanded. However, after three years of self-management I believe we have found a model, a structure, which works.

Retirement villages offer freedoms

Today it is perhaps more appropriate to ask the question ‘why, in this country, are 70 year olds not rushing to embrace the freedoms of retirement living? In some countries 20% or more of those over 60 move to retirement complexes.

For the few who do move in the UK, in my experience the main reasons are distress related:

a) a sick partner and so the need to be near help;

b) family deciding that parents cannot cope and forcing them to move but occasionally there are positive decisions such as:

c) a wish to be near grandchildren.

d) and those with no near relatives planning for their own future whilst they can

It is interesting that those with no near relatives make the decisions early. Maybe my wife and I, who have close family living nearby, are exceptional but what right have we to neglect the inevitable future and leave the burdens of our ageing to them?

I venture to suggest that it is not just the lack of suitable sites and planning approvals which are the factors in the low take-up of leasehold retirement homes. Fear is a powerful factor:

Fear

1. Fear of loss of status in downsizing to a retirement ghetto

2. Fear of leasehold – horror stories in the Media

3. Fear of lack of control over future costs of the annual Service Charge over which there is no immediate, and little effective long-term, personal control

4. Fear of the landlord’s right to add to and remove services

5. Fear of not been able to resell if money is wanted quickly to pay for intensive care

6. Fear of losing one’s independence

And, may I suggest,

7. Unsuitable homes – The lack of attractive, suitably designed, retirement homes, with at least a large living room, a study, and two double bedrooms, to attract active 70 year olds as opposed to the minimalistic flat offering forced to moves in 80s. Finally, maybe we retired folk do not wish to acknowledge we will get old, with physical and mental problems, and so do not plan for it.

What do people value?

Independence

Own front door onto open space. They do not want a block of flats with doors onto corridors.

Financial assurances that there is control of charges and a resale market.

Power to make decisions which directly affect their lives.

Living space

Fewer but not smaller rooms. We have found that one bed flats are slow to sell.

Private space – maybe a small garden but also village gardens to enjoy.

Fitness for purpose with design considering future limits to mobility.

Long term assurances of companionship.

Support services when needed.

Ownership and, with it, the right to participate in decision making.

There is nothing wrong in developers making a profit from retirement housing but they do need to rethink what are their customers’ needs, if they are to attract the active retired.

Leasehold retirement villagers need the assurance of special legislation, separate from current leasehold law, which empowers them to manage their chosen life style.

Otherwise, we may have to accept the alternative which is that retirement villages are just ghettos, half-way houses, for the physically and mentally infirm who can be easily overcharged.

The vast majority of those over 60 are not incapacitated and a fifth have, we are told, property and other assets, worth over £1m and many more are pension rich.

They are intelligent and will choose to manage their life style. If they cannot find suitable retirement housing they will stay in their present family homes and later – too old to move – become a burden on social services.

Peter Wilson

Woodchester Valley Village

Inchbrook

Nailsworth

Gloucestershire

GL5 5HY

01453 837703