The body representing the most powerful interests in British property fully supports greater regulation of the leasehold sector – leaving Housing Minister Grant Shapps isolated in blocking regulation.

That was the main finding of LKP’s meeting with the British Property Federation’s chief executive Liz Peace and Ian Fletcher, who heads the BPF’s residential division.

The BPF had in fact lobbied in 2010 to stall the introduction of sections 152 and 156 of the Commonhold and Leasehold Reform Act, which was actually passed in 2002.

These protections to safeguard leaseholders’ money were in fact jettisoned by Shapps as soon as he took office in May 2010.

The BPF’s objections were that the sections were poorly drafted and the time-scale was unreasonable, but the basic principle – that leaseholders’ money should be better protected than it is now – was not disputed.

There is near unanimity on this – in theory – in the leasehold world, including among the trade bodies such as RICS, ARMA and the ARHM, and the BPF’s clarification will be hugely influential.

The London Assembly last month added its weight to the argument in its hard-hitting report on “opaque” service charges.

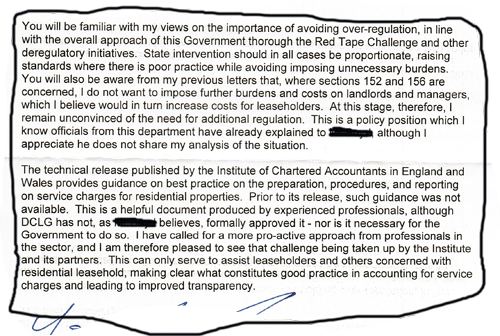

The only person who appears to believe there is balance in the system is Grant Shapps himself, who again in a recent letter to Zac Goldsmith MP, reiterated his opposition to improving the position of leaseholders.

He believes that greater protection will over-burden landlords and has an ideological aversion to regulation.

But the taxpayer-funded Leasehold Valuation Tribunals, which were supposedly low-cost simple tribunals, would benefit from clearer regulation.

At the moment, they are hugely weighted in favour of landlords, who play the system, repeatedly demand appeals and routinely employ counsel at hearings.

Whereas landlords can spend whatever they wish on legal representation – and, if they win, claim these legal fees out of the service charges – leaseholders can only win back £500 of legal costs.

The LVT battles of Charter Quay, St George’s Wharf and Chelsea Bridge Wharf all involved £20,000 to £30,000 of legal costs on the part of the leaseholders, and far more from the landlords.

The current inadequate LVT system does not represent good value for public money.

Compared with tenants in assured shorthold tenancies – whose deposit money has to be placed in a tenants’ deposit scheme – the position of leaseholders is astonishingly vulnerable.

Between £1 billion and £2 billion is paid by leaseholders in service charges every year – with £500 million in the capital alone, according to the London Assembly – yet there is hardly any protection for these funds at all.

They are simply held and used by the managing agent until such time as he choses to submit his accounts – and they need not arrive until up to 30 months after the money is spent, according to a recent a decision by the Upper Tribunal.

By that time a leaseholder may well have sold up, moved on or died.

For years the professional bodies have done very little to enforce their window-dressing codes of practice. Indeed, some of them have done their best to shelter the worst rogues in the industry.

Even the worst of these organisations now wants better regulation